The title of this work Selfish Tree is an oxymoron. It is not in the nature of the tree—if we have to say that—to be selfish, but this particular tree seems to have appropriated anthropomorphism in reverse. That is to say, instead of humans attributing human characteristics to the tree, this jackfruit tree anthropomorphised itself. How else can one explain this peculiar mimesis and self-appropriation, and the strange behaviour of this tree that would not allow its fruits to be consumed by any other living being? Especially, when alive, it was revered as divinity and tended to with care. Suresh’s installation by adopting the tree and its story and entitling the work with juxtaposition of terms with their laden significations, “selfish” and “tree,” is an allegory of human “self-interest” as the binder of modern society, elevated to a level of virtue in neoliberalism and effectively deployed through an innocuous notion of “entrepreneurship.” An entrepreneur is the one who is driven by self-interest, he is self-reliant, opportunistic and his success—always measured in terms of monetary accumulation—is the mark of his entrepreneurial quality.

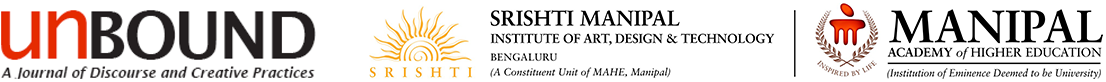

Suresh Kumar, Selfish Tree, 2001-02, details. Courtesy of the artist.

On another level, Selfish Tree revels the possibility of other three installations in the series: Wade, Harvest for Better Monsoon and Lifeline and their conceptual profundity. One significant element of the Selfish Tree is the story narrated in Brail script on the grounded sections of the installation. The story, inaccessible to scopic modes of sensing, can be “read” only through tactility. The immanent critique in Wade, Harvest for Better Monsoon and Lifeline of visible transformation of Indian life in general, and Bangalore city in particular, are possible only through mobilization of all sensible capacities of body, otherwise the critical operation remains incomplete. Walter Benjamin said, “Criticism is a matter of correct distancing” (Benjamin, 1978, 85). Distancing is not a physical and spatial separation from the reality under criticism, instead penetrating it with all senses to reveal the fissures. What emerges, as work of art is the configuration of elements gathered in this surgical operation.

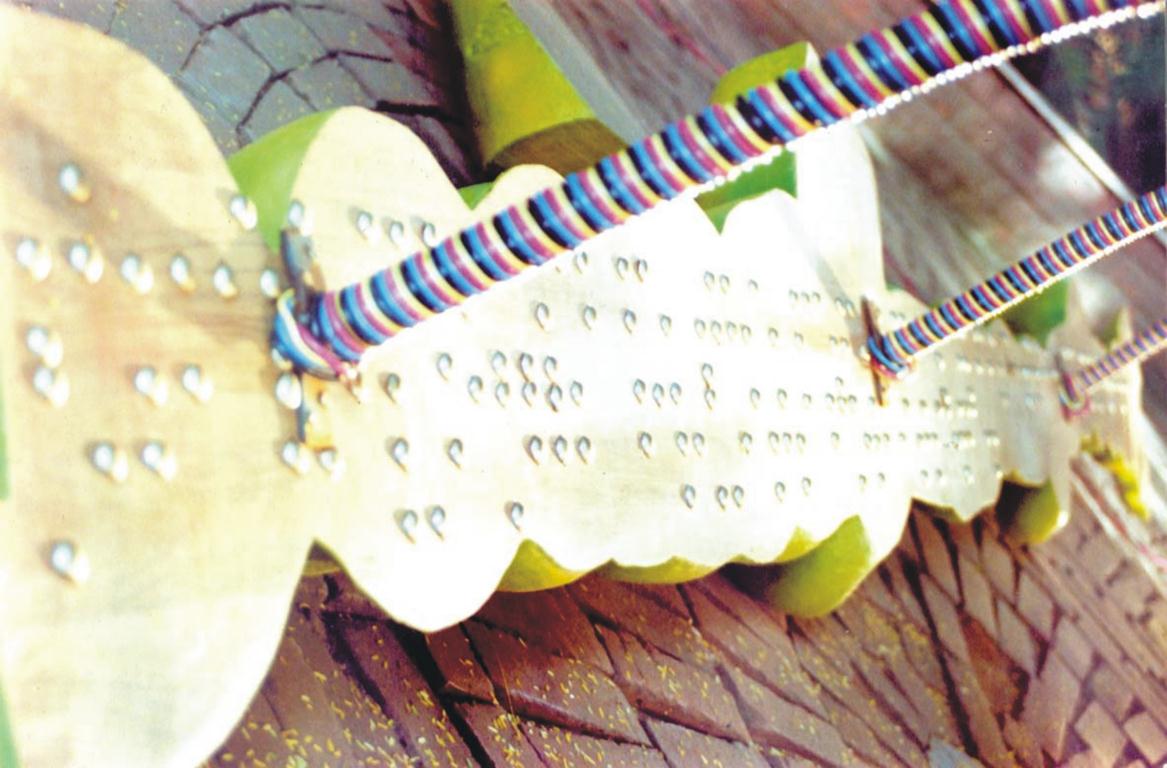

Suresh Kumar, Selfish Tree, 2001-02, details. Courtesy of the artist.

Capitalism is apt at, as French philosopher Jacques Rancière observed, transformation of things into signs (Rancière, 2009, 45). It is the same procedure deployed so successfully for so long that it blindly follows it with little variations in every life world it conquers. In the first modernist phase of India—for 25 years after the independence— State controlled large-scale industrial projects; irrigation works and institutions were projected as the nationalist symbols of self-reliance and modernization. The second modernity that subsumes or obliterates national in favor of the global does not offer any such symbolic or monumental constructs, instead it proliferates signs that produce reality effects. A critique in this order, as has happened with postmodernism in all its variations, often is a matter of producing, with ironic distancing, further signs through recombinatory operations. The ineffectiveness of these maneuvers are there everywhere to see, because the symbolic order is adept at assimilating and transforming all “things into signs,” even other signs. Suresh’s work reveals another possibility of critique: allegory and through allegory the effective possibility of deconstructing the symbolic order or even resisting it.

Allegory, as Benjamin wrote in The Origin of German Tragic Drama, is not a “playful illustrative technique, but a form of expression, just as speech is expression, and, indeed, just as writing is” (Benjamin, 1985, 161). As an expression, it is neither a symbol nor a representation; instead it is assembled through object-fragments wrested from reality. These remnants are examples and instances of reality from where they have been gathered. In Wade, the grain storage containers shapes are compiled with construction steel bars, layered with ragi millet filled bricks stitched from Flex material printed with computerized images of new constructions. In Harvest Better for Better Monsoon, the silk sari is woven by displaced weavers using leftover yarn in their homes with dried sprouts picked up from the fields serving as decorative motives. All elements used by the artist in the creation of his works preserve their bare materiality, stripped of any hidden ideas or references. This absolute transparency and the direct relation between the particular and general is what accords these works their allegorical character. There are no symbols to be decoded, there are no hidden meanings to be deciphered and above all there is no irony, instead Suresh’s installations are assemblages of fragments to be read and understood by any discerning viewer. What the remnants gathered together in these works of art reveal is the ruinous nature of reality and the “irresistible decay” of the present.

If the old Nehruvian modernity lies in ruins today, the new global modernity is erected like a ruin.