Suresh’s father’s family were landless peasants from Chandapur, who cultivated other’s land on lease. It is drier than Sarjapur, they couldn’t always depend on agriculture for livelihood so they had to go out and find other work. That’s why his father left the village and got training in an industrial training unit near Dairy Circle and then got a job in a newly established Public Sector Undertaking (PSU). Before the IT boom in Bangalore, there was the Public Sector boom: Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), Bharat Heavy Electronics Limited (BHEL), Indian Telephone Industries (ITI), Hindustan Machine Tools (HMT) and others. While IT stands for the second wave of modernity, PSU was the symbol of the first modernity in India. Each was founded on a different understanding of the role of state, democracy, citizenship, nationalism and the idea of a nation, and consequently manifests differently in the everyday life.

Suresh’s father’s job brought the family to Bangalore city. They started living in the Wilson Garden area of Bangalore, because his father found it difficult to adapt to the city and staying on the road leading to his village would make his city life bearable. A few years later, his father fell ill and owing to financial difficulties and other issues, the family had to move to their village near Sarjapur. However, Suresh’s mother who was holding everything together in these difficult times was keen that they should continue in the convent English medium school they were enrolled in. Convent was attached to every school name that wanted to project an image, whether run by the nuns or not. Any school that taught English and had aspirations was called a convent. By the late 80s however, Convents lost their cache and was replaced by Public School as a suffix for school names. With neoliberalism, “international schools” have come into vogue and occasionally one encounters the nomenclature of “global or world school” as differentiators from the mere “international.”

After the family moved to village, Suresh and his sister started commuting 30 kilometres in a Karnataka State Transportation Corporation (KSRTC) bus each way from village to Wilson garden, to attend the school. If they missed the first bus, they would lose two periods in the school because the next bus from the village was an hour or hour and half later. The six years of commute, from 1983 to 89 was quite a journey. They shared the bus with milk vendors who brought milk every morning to the city from their village; farmers who brought flowers and other produce; few employees with government jobs. For Suresh it has always been the bus. Bus is the connection to people and life. Bus is the place to work, not just commute. People ask him how does he get so much time to be active on six Whatsapp and Facebook accounts, and everything else that he does in addition to social networking. Traveling in the bus gives him all the time he needs.

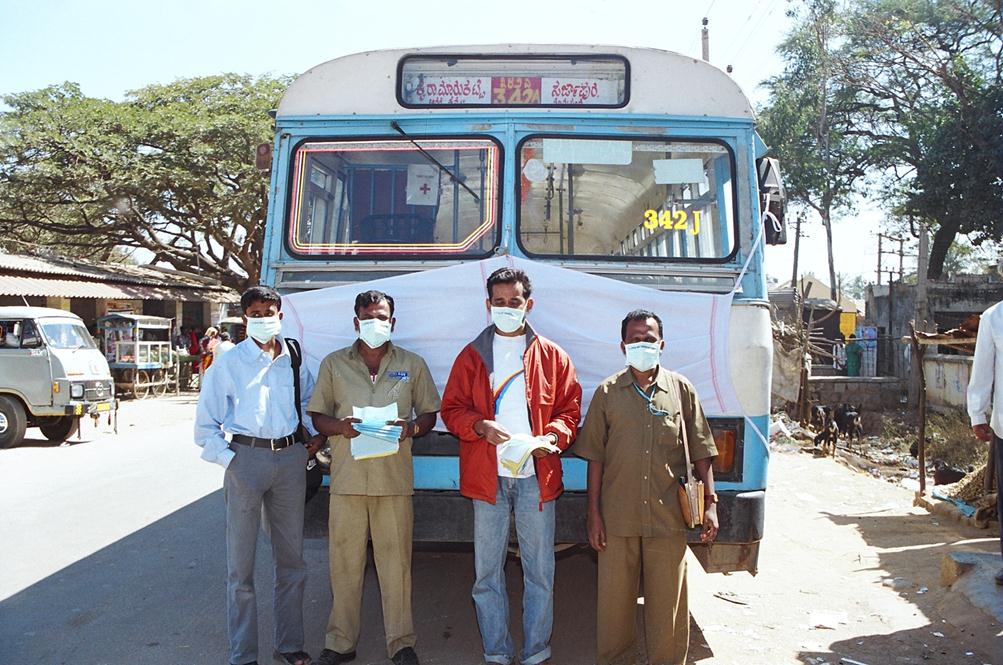

In 2004, when Bangalore City Transport Departments invited 60 or so artists to intervene with their work to encourage people to take public transportation, he got a chance to make the bus, the commuters and the journey central to his work then. While most of the artists involved worked on painting the buses, Suresh located his work inside the bus. He was not interested on the surface. So he travelled the whole day in a bus that came from the village to City market in Kalasipalyam, the same bus, as children, he and his sister took to come to school everyday. In this project, the artists were given an urban context to send a message to people to bring about awareness on the problems of urban transportation and encourage them to use public transport to reduce congestion. Suresh reversed this context by shifting the point of view to village. It is now the villagers looking at the city instead of city looking inward. His audience as well as active participants were the college students, job seekers, employees and farmers coming to the city from village to inhale the polluted air, to be subjected to congestion, traffic and constrained spaces.

Suresh rode the bus the whole day wearing a surgical mask that said “I Love Bangalore”, similar to famous t-shirts that have “I Love NY” printed on them. He distributed surgicalmasks to all the passengers who got on the bus. They were hesitant in the beginning, but once he explained to them, they took it seriously. He also put on a white mask on the bus to see how dirty it will get in one day. He was not interested in creating a symbolic piece for display to be seen by the passengers, instead he wrote a pamphlet in Kannada and distributed the same, along with masks, to the passengers.

Suresh Kumar, Bus Narratives, 2004. Courtesy of the artist.

Suresh Kumar, Bus Narratives, 2004. Courtesy of the artist.

It was at this juncture that Suresh started moving away, as an artist, from object making to experimenting with live performances. Before that, as an artist trained in sculpture, he was producing art objects and installations. Although they were all rooted in his experience of places, people and relationships, they were still objects to be displayed and seen from a distance. With the Bus Narratives, Suresh began experimentation in blurring the distinctions between a work of art, audience, context, reference material, source and inspiration. The artwork ceased to be an externalized material object with form to be displayed in designated spaces and viewed from distance in silence; instead it emerged in a process of interaction between the artist, audience and context. The audience themselves were transformed from observers to participants and the art experience changed from private contemplation to active contribution. The artist role too changed from a producer of aesthetic object to an interventionist who reconfigures the arrangement of everyday event—the bus journey—by introducing new elements that alter the phenomenality of the journey and the places from which the journey originates and ends. The people in the bus commuted everyday from the village to City Market for jobs, to go to college, to sell their produce, for shopping etc. They always looked at this journey as purposeful; to accomplish a task. Suresh’s intervention with masks and pamphlets brought a new dimension to this experience. It is now a journey from open spaces to constricted and congested places; from fresh air to a polluted atmosphere. Along with the experience, there is an alteration in the consciousness of the people both in regard to the places they journey from and to, as well as their own location within these places. This transformed consciousness and consciousness of their own position is distinct from an aesthetic experience of novel imagery on the side of a bus exhorting the virtues of public transportation.

Until high school Suresh did not know art. He was good at making models, copying things, rendering from images exactly what was shown. A lot of people around him, his schoolmates especially, thought he would become an engineer since he was good at making things. After finishing 10th grade, he could not join Chitrakala Parishad (CKP), the art school in Bangalore, as his father couldn’t afford the tuition. He had to wait 2 more years before he could. During the intervening period, Suresh’s father had bought a plot of land somewhere between the village and the city and built a small house with asbestos roof and a garden. Suresh took up gardening and thought of opening a nursery in the village without actually knowing what it all meant.

His experience at growing a garden and trying to open a nursery were later connected with his ATP Kiosk (2004) project. It was a time when ATMs were springing up everywhere in Bangalore. He thought why can’t there be ATMs that give out saplings, instead of money, so that people can plant them in the city, in their backyards and gardens. It was more like a proposal to the government. While gardening in his front yard, he thought of planting lot of trees in his village so he went to the Forest Department to get saplings. They made him do lot of rounds without actually giving him a single plant. All the schemes on social forestry that the government promoted had little impact on the ground. So he came up with the idea of a sapling dispensing ATM Kiosk called ATP.

Suresh setup an ATM like kiosk on MG Road during the first edition of Bangalore Habba, and if someone inserted a business card, a plant would be given. There wasn’t any machine like in an ATM, dispensing the saplings. It would be either Suresh or some other person handing over plants standing inside the kiosk and dressed in costumes. They distributed over 500 saplings. One of the conditions for the people taking plants was to mark on a Bangalore map on a table where they would be planting them. Suresh dreamt how the saplings he gave away would occupy the city and grow into large patches of greenery like Lal Bagh or Cubbon Park.

Suresh Kumar, ATP, 2004. Courtesy of the artist.

Suresh Kumar, ATP, 2004. Courtesy of the artist.

With Bus Narratives and ATP, Suresh began to explore other artistic practices that intervene directly into the dynamic and fluid spaces of public interactions, instead of being in a controlled environment like a museum or a gallery. The artistic installations, Wade, Selfish Tree and others as allegorical expressions are visible configurations of remnants, which maintain a palpable distance between the allegorical expressions (assemblages) and the reality. The projects that Suresh has been engaged in since the ATP Kiosk and bus narratives tend to erase this distance and turn the work of art into intangible happenings. In the transition period between the installations / objects and “projects”, Suresh created many site-specific works that both materially and conceptually disintegrated the moment they were completed. The allegorical mode of installations and the ephemerality of site-specific works come together to form Suresh’s current artistic practice. His work, temporally and spatially bound, and that employs allegorical as the principal artistic mode is difficult to classify into any known artistic forms—interventions, performance, street theatre and others.