Debbie Whelan, University of Lincoln |

Introduction

Fed-up action on litter, Taking back the city’s streets, Vagrants defile post office[1] are all newspaper articles penned in recent years speaking of Pietermaritzburg, the City of Choice and the capital city of KwaZulu-Natal. There are many, many more examples bemoaning change, development, nostalgia. They all speak to a series of systemic challenges, which African cities face in contemporary times. In South Africa, the issues are exacerbated by poverty, lack of education, ignorance and reprioritization of national, provincial and municipal budgets in order to alleviate the strains of these challenges. Nearly a quarter of a century after South Africa achieved democratic freedom, many small towns and cities in KwaZulu-Natal are drastically altered from their colonial-era European-inspired spatial planning and values, based on hierarchies of urban space around the central market, an attention to streetscape and urban quality, and construction of memorial and memory. These city centres now demonstrate a gradual erosion of public space, in which the vectors of transport are prioritized, the car, the minibus taxi and the pedestrian, rather than a ceremonial space, which contained memory, provided a refuge from the sun, a place to spend time, and to meet. In most instances they have become spaces of irrelevance, through which people pass, and for which, the new city governance has little interest. This is exacerbated by the changed priorities of the politicians, in which the emphasis is on accommodating the majority, as opposed to the few. Physical manifestations of this include cities that have lost their centre, which spend much time renegotiating identity, exacerbated by changed political stance particularly towards Colonial-era statues, which began with the #Rhodesmustfall campaign in 2015. Further, the comment is not on a nostalgic resurrection of the ‘old days’ but an attempt to understand why urban space in these city centres has changed, in order to feed back into development viable means of constructive planning and prioritize heritage protection where possible. This is done through considering how local people, largely the Southern Nguni and more politically the Zulu, perceived space in history. If different understandings of space are a product of culture or an understanding of culture, then perhaps we can reconfigure how we should think about space in a new South Africa, in which the white settler no longer determines how space is used, but the quotidian user of the contemporary city.

Image1. Central market square, Pietermaritzburg (Author 2017)

Pietermaritzburg is of specific interest in this issue: the Old Market Square, known also as Ndlovu Square and Freedom Square, has gradually been eroded by buildings demonstrating reactive planning, little character, and limited practical use, resulting in an incoherent urban space which has little merit. This is largely the fault of the authorities: the Msunduzi Municipality facilitated development on the square, a Provincial Heritage Landmark, without recourse to the heritage authority, which had the power to assist in regulating quality of design and spatial planning. Other post-1994 decisions allow for further changes, such as the emphasis on covering the square with parking, as well as a minibus taxi rank. This has resulted in polarizing the urban space and emphasized those generators of movement and escape from the inner city, as opposed to providing spaces in which people happily spend time. There are benches, but the space is difficult to access with any flexibility. People move around the site and rapidly across the site, and there is little to attract people to spend time there.

The production and use of urban space in South Africa’s cities is heavily influenced by its social and political history. KwaZulu-Natal began as the Colony of Natal, a British territory supervised initially by the Cape Colony and then, after 1897, through self-administered ‘Responsible Government’. Public space was white, English in flavour, with a hint of Dutch dating back to the original settlement in 1838. It contained associations of which the white citizens were proud, such as statues erected publicly or by subscription, gardens carefully tended by employees of the city departments, benches, pavilions, water fountains and other sundry follies. Most of these items, heavily derived from an European aesthetic and cultural framework, landed in the cities and towns as part of the re-describing of a ‘little England’ particularly on the colonial city fabric. This had limited relevance in a new country in which a majority aboriginal population, ignorant or dismissive of the western origins of the ruling settlers, occupied the space.

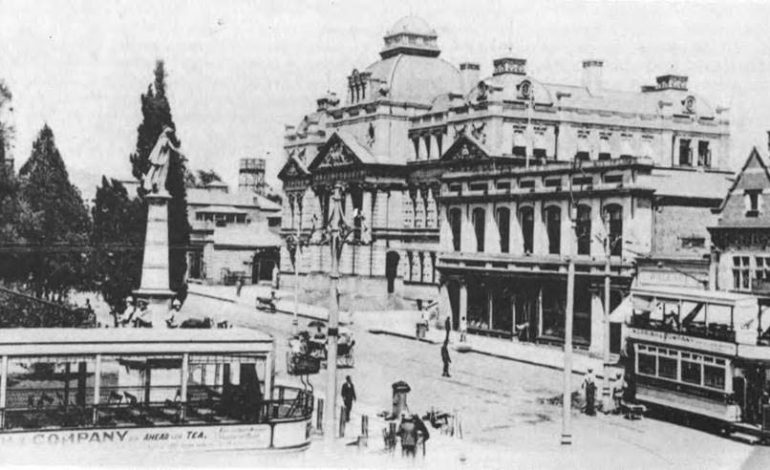

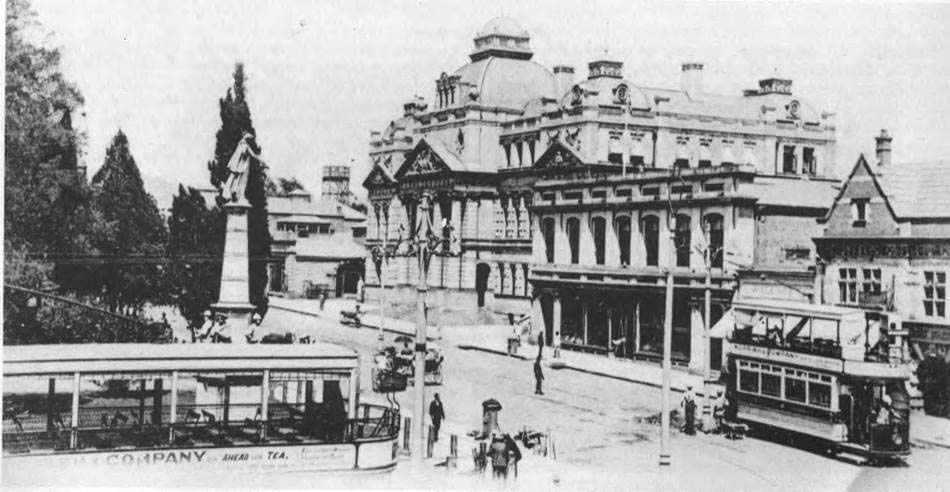

In the late nineteenth century, Pietermaritzburg had a shifting, cosmopolitan population, particularly as a centre for operations during the Anglo-Boer War. Discussions had been held around a ‘model native village’ as early as the 1850s,[2] which sanctioned the residence of Africans within the city, as they provided labour for the immigrant settlers. At the same time, for the initial decades of the twentieth century, the cities were the realm of the settler, under the control of the settler, and managed by the settler. Municipal Native Affairs Commissioners administered the finances for the provision of facilities for African residents, channelled through the Municipal Department of Native Affairs and funded by the proceeds of municipally-run African beer halls, themselves a destination and a stop on a journey, rather than a publicly negotiated public space.

Image 2. Pietermaritzburg city centre, 1906. John Laband and Robert Haswell, Pietermaritzburg 1838-1988, a new portrait of an African city (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press and Shuter and Shooter, 1988), 92.

After the dismantling of apartheid, a shift from the controlled use of colonial-era generated space by the Nationalist Government prior to the elections in 1994 began: the collapse of exclusionary legislations such as the Native Areas (Urban) Act, those legislating for the carrying of ‘passes’ and the different Group Areas acts promulgated between 1950 and 1966 meant that space took on new meanings for everyone. Importantly, a rapid rural-urban migration occurred, which created new city users, in addition to the new politics of the new dispensation. The city centre gradually began to change, raising the ire of the established white residents as the changes did not subscribe to their particular worldview, creating tensions with management, planning and maintenance.

Trading places

And thus one turns to history and historical anthropology to establish what the fundamental expectations of the new immigrants to the contemporary city are. In order to understand this, buildings that describe space, practice and inversion will be discussed. These were independent, white-owned community stores established to trade amongst, between and within communities in the Colony of Natal.

The ‘trading store’ flourished in Natal Colony and then the Province of Natal after Union in 1910. Country stores located in rural areas, for many years of the late nineteenth and early to mid-twentieth century, dominated the rural landscape as the single point of purchase of colonial manufactured goods, and indeed, distribution of African produced goods. Typically, and vital to the discussion, they were orthogonal buildings introduced into an architectural landscape that was largely circular, people of the Southern Nguni historically constructing homesteads based on the circle. They were also places of enigma: the commercial success of the trading store depended to a large degree on the space that it commanded and the manner in which this was negotiated. How it was filled with texture, colour and smell is the stuff of nostalgic cacophony,

A native store in lower Africa has little visible arrangement, the eye and nose being simultaneously taken with a medley of gay fabrics, sticky candy, loose cookies and strongly smelling boots. Whether or not it is large and prosperous enough to command a cleaner and tidier European section, there exists a tacit understanding that this is primarily for native trade, and that rightfully, natives meet and idle here.[3]

Typically, trading stores were white owned, situated in or close to a district ward or igodi managed by an iNkosi, or chief, or one of his headmen or iziduna. The original stores consisted of a general central space of trade, around which ran a counter, behind which goods were situated. In more prosperous stores, a longer counter allowed for a number of staff to operate sections. Different assistants were responsible for different goods. The ‘smalls’ counter sold beads and cottons, there was often a fabric salesperson, and another person dispensed flour, sugar and tobacco into paper wraps or small calico bags that customers brought with them. All items were purchased through the storekeeper and this person as interlocutor, assisted in the negotiations of trade. The length of the counter allowed for the ritual of item-by-item purchase, providing for group participation and public scrutiny of the process. Counter service stores became richly functioning spaces which held the heart of discussion, transaction and purchase ritual.

Purchase ritual itself contributed fundamentally to the experience of exchange. An item would be sought, examined, discussed, analyzed, put back, another item taken down, and the same process followed for the next item. Shopping was a community exercise. What a customer purchased was discussed and sanctioned by other customers who would join this ritual. Eventually an item would be chosen, the price discussed, and the laborious process of disentangling money from the folds of a shawl or head dress or tucked in a bosom would ensue. The money would emerge, be slapped on the counter and the trader would take the money. The change would be returned to its hiding place and the process would resume. This incremental purchase was an event and it could take hours.

Thus, the event of the trade was as important as the trade itself. Whilst Noni Jabavu has a very evocative description of the process of trade, the noise, the smell and the activity,[4] section 13 of the 1955 Report of the Tomlinson Commission records more soberly of the customers that,

They are slow, deliberate buyers and may spend hours in deciding over a particular small purchase. They like goods to be freely displayed, as this gives them a better chance of examining and feeling them at leisure, while they often harbour suspicion about goods not so displayed. Haggling over prices is a common spectacle, and the Bantu is considered a good haggler. He regards himself as a good judge of quality.[5]

Image 3. The inside of a trading store in the rural Transkei, 1966. R. Savage, A Study of Bantu Retail Traders in certain areas of the Eastern Cape (Occasional Paper no 9, Grahamstown: Rhodes University, 1966)

The need to purchase individual items singly, to count out the money, to engage in banter and drama, all foregrounds the relationship between the customer, other customers, and the trader. The measured way in which this process was enacted, ensured accountability and entrenched a freedom of choice in a country in which, for Africans at the time, scarcely existed. In addition, it provided for a platform of power over the trader by the customer, allowing space for the accounting amongst a largely innumerate group. The Report of the Tomlinson Commission was specific about customer practice, stating that the choice of ‘particular shops….is based chiefly on the integrity and personality of the shopkeeper’, and old traders tell of people walking further to a specific store because of these qualities. At the same time, the need to save a few pennies would entail people walking a long distance. There was no routine spending pattern: people would spend small amounts of money when they received them. The Report of the Tomlinson Commission concluded that haggling and an ‘eye’ for a good price resulted from the need to use a small amount of income effectively.

It thus appears that – (i) the Bantu customer is not content with just any article offered him and that the trader must choose his stock judiciously; (ii) the Bantu customer prefers to choose his purchase from a variety of articles, which increases the investment in stock; (iii) the Bantu attaches great value to the integrity and personality of the trader; and (iv) he likes to make his purchase leisurely.[6]

Early trading store floors thus provided an open space for communication and dialogue. They were conceptually comprehended and accepted spaces in which the ritual of trade was played out. Rather than being insular and personal, this established drama involved all the customers in the store and provided reason and means for people to travel to the store to shop. The store represented an inverted, culturally neutral space.[7] In addition, for a long time, this was a largely liminal space in which both trader and customers lingered on thresholds of mutual relations. The trader was at the mercy of the customers as far as this intense and dramatic process of trade was concerned. For many traders, the only way that they could claim any space for themselves was by closing the doors.

Indigenous space

This ‘open’ space of commerce was unusual for local people who had a much more closely prescribed spatial understanding. Indigenous planning amongst the Southern Nguni provides few formalized communal meeting places that are not partisan. Families occupied separate and distant homesteads under a umnumzane, and ‘public buildings’ apart from the military homesteads known as ikhanda, were not as elevated as ‘the great place’ as suggested by Wilson et al.[8] The King’s homestead would have been the most important place through association and power, and not through mutual practice and community brokering. Communal space operated rather as part of an inhabited landscape, a lineal and dynamic one along paths, nodes, and rivers. What Hourwhich Reyer terms the ‘native centre’ was thus for the Southern Nguni a new form of space with intrinsic protection since it was not associated with a specific political power. Hilda Kuper said of the neighbouring SeSwathi that pre-colonial perceptions of space were autonomous and tied together with political allegiance, which allowed for flexibility, unlike the Colonial impositions of formal boundaries of civic control. She thus connects the view of space to people instead of delineated boundaries.[9] This reinforces the partisan nature of the Natal landscape for the Zulu, and inserts traders and their stores into a more complex interface of spatial perception. This connection of land and space to people is reinforced by the statement around land of King Cetswayo kaMpande (1826-1884), a significant leader in the late nineteenth century:

All the land really belongs to the King, but [a] man has leave from the King to live there, and take care of it for the King. But if the King thought proper he could deprive him of it, or remove him to another place. – No, a man is not deprived of his land. If he does anything wrong, they tell him he ought not to do such a thing because his father did not. ….they do not mark it [land] artificially; it is defined by rivers and hills. The boundaries are looked after by the headman … if the people in one district wish to cultivate land in another, they must get leave from the King [a man knows which land to cultivate when] A party from each part of the land goes to a certain place, and they see something that grows there, and that is the mark of the division.[10]

The statement of Ndukwana kaMbengwana, recorded by James Stuart in 1900, reflects that.

There were no restrictions as to where cattle might graze, for there was no such thing as a boundary. They could go by or even through, other peoples gardens so long as the standing crops were in no way damaged, and provided there was someone present to look after them carefully. Not only did the whole land belong to the King, but the whole of the cattle as well [11]….Paths, private or public, slightly used and greatly used, traversed the country in all directions. There were no such things as roads, for there were no wagons. In no place could a man be said to be trespassing; there was freedom or right of way in all directions [12]….People coming from countries like Tongaland preceded (sic) along the main and well known paths. All paths ultimately found their way to the King’s kraal…In Tshaka and Dingana’s times there were no such landmarks as boundary pegs (izikondwane); land was divided and defined by means of streams, hills etc; nor were stone beacons used, or trees, as defining boundaries. There were no stone beacons in Mpande’s reign.[13]

The Natal Code of Native Law was officially promulgated in 1891 although as a framework it had been operating for some years. It lays out the rules for engagement for civic matters as adjudicated by the amakhosi in tribal courts, and seeks to regulate aspects of Zulu culture, such as the number of lobola cattle, used as bride wealth in marriage. For land tenure, the Natal Code of Native Law indicates the following:

All grass lands in Native Locations, are open to the common use of the Natives lawfully residing in such Locations; provided that small patches of grass of recent growth (inlungu) situated in close proximity of occupied kraals, may be reserved by the heads of such kraals for their private use…Every path, road, necessary cattle track, and watercourse hitherto open on Location lands, and in use by the tribe or members thereof, shall remain open and to the use of the tribe and to the public generally’ [14]

Constant reference to paths, rivers, and cattle tracks reinforces the dynamic nature of the consideration of space, in addition to which a strongly situated land patriarchy with respect to the association of land with specific people, and not civitas suggests that space itself has an alternative world view, heavily reliant on the construction of power and the brokering of people and cattle. Whilst places may have been named, which accorded them status, power also regulated their use, these were still associated with a specific power structure and respect accordingly paid.

On a more intimate level, the individual homesteads were equally politically structured. John Argyle and F. Buthelezi investigated the occupation and perception of space within a Zulu homestead and a single dwelling unit.[15] Working from the general knowledge that the individual dwelling unit had a strong correlation with the binary of left and right, in which the left was the woman’s side and the right the domain of the man, they determined that this generality was further fragmented into a more specific set of rules. These determined where a person was expected to sit in a single dwelling unit, reliant on a relationship to the household head and age. Thus, the occupation of a small structure was governed by a highly sophisticated set of rules, which existed to create order and ordering.

The single dwelling and the structures around were sited according to status, age and gender, and to some extent, it was a microcosm of the entire uMuzi (homestead) with its rules and regulations. Within the single dwelling unit was ‘invited’ space, and one which was negotiated through belonging to the homestead, in which a family member was aware of their space and their place in the homestead and, too, the society of the Southern Nguni people in general. Outside the dwellings, open to the sky but contained within the all-embracing uThango stockade, was culturally determined space, subject to law and hierarchy. A central cattle byre was the domain of the man, the domain of power and the domain of items to be protected.

Social, cultural and temporal transitional space

This highly protected space of the family, and the ruler, then contextualizes the conflict in perceptions of space between aboriginal residents and the urban space introduced by settlers from Europe. For in the foundations of western derived worldviews, in urban spaces, the diversity of society is important. Hannah Arendt discusses Aristotle and his definition of the word polis indicated as ‘a community of equals for the sake of a life which is potentially the best’ and ‘is composed of many rulers’.[16] The Agora in Greek times allowed for multiple participation and negotiation of public space. Sophocles noted that ‘a polis belonging to one man is no polis’ and, as such, a dominant ruler ‘deprived the citizens of that political faculty which they felt was the very essence of freedom’.[17]

Image 4. Traditional homestead ca 1890. KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Archives Repository, Usuthu Kraal, C8467.

For the Zulu, the space within and without the trading store, an alien construction of space, was then differently circumscribed. In some stores, the trader attracted people from two different tribal groups, and in the store, the enduring presence of the power of the iNkosi was neutralized. From a social point of view, the trading store floor had no political overlay, rather a negotiated space between buyers and the trader; this was, thus, a new ‘form’ of space.

Architecturally, for a long time, the trading store was orthogonal, an anomaly in the land of the circular. Further, it contained a vital space rarely seen in the traditional buildings of the Southern Nguni, a veranda.

The veranda is an intrinsically colonial response. Whilst he acknowledges its presence in Regency era buildings in England, Ronald Lewcock noted that it was,

…an integral part of the South African scene that it today would be inconceivable for us to imagine nineteenth century architecture without it. On the farms it gave rise to the typical post-Trek farmhouse, encircled (or at least fronted and backed) by low lean-to roofs; in the towns it blossomed forth in tier upon tier of colonnades and lace-like tracery.[18]

In order to understand the place of the veranda in the importance of trade, a comparison was drawn using a tool situated in the colonial era, the Marsh Catalogue for prefabricated ‘wood-and-iron’ buildings.[19] Smaller ‘cottages’ were compared with those advertised as ‘country stores’. Using the dimensions of the main building, the store and the veranda as provided in the catalogue reveals that the latter provided a large amount of extra ‘real’ space for the trader.

In the smallest ‘Country Store’, the veranda comprised 88% of the total building size. This is significant, suggesting that the veranda was intended to operate as an external circulation space for customers in lieu of available internal trading space. This function is highlighted since the ratio of veranda-to-store space was consistently above 40%. Thus, the veranda as a ratio of the total structure for the stores, at least, did not drop below one-fifth of the available space. This comparison can inform the following observations:

- The veranda served as a practical extension of the trading space, containing customers and offering shelter, as well as assisting by climatically controlling the interior. It occupied a substantial portion of the footprint of each building.

- It is impossible to interpret non-empirical information such as the function of the veranda as an interstitial space between the ‘world’ and the ‘comfort and containment’ of the store. However, there is an undeniable movement from release to constriction (space to containment) and vice versa (containment to space) passing each way through the transitional space of the veranda.

- In most of the cottages examined, that were intended for urban use and heavily prescribed by colonial culture, the veranda leads either into a ‘public-private’ hallway or into a lounge. As noted, the process of approach to a private urban dwelling passes through a series of layers: entrance through a gate, down a path, and access across a veranda. Thus, when entering a private urban dwelling via a veranda, when the front door is reached, the relationship is already more intimate.

- In the store options, the immediate ingress into private spaces diminishes the layers of approach common to the urban dwellings of the time. There is little process of arrival in leaving a very public space to enter a private space. This immediacy suggests that the trader’s private life was not spatially removed from his/her public life.

- The diagrams depicted display the provision of a moderate level of privacy, much less than would be deemed acceptable in a Victorian or Edwardian household, let alone a Zulu uMuzi

With time and the passing of generations, this spatial distance appears to have become more learned, more described, and more intended. Spaces that accommodated the more intimate dealings with customers, such as legal advice and access to accounts, were either carried out in the office or on the peripheral veranda space. On exceptional occasions, customers were invited into the living area of the traders, an action that would rarely be reciprocated. Thus, it can be inferred that the early traders, by dint of the immediate access into personal spaces as indicated by the planning of the stores in the Marsh Catalogue, were implicated in, and exposed to, the community.

Thus, this mutual spatial ownership of the store and the realization that the trader lived largely in the realm of his customers is contextualized: Christopher Alexander noted that ‘No building ever feels right to the people in it unless the physical spaces (defined by columns, walls and ceilings) are congruent with the social spaces (defined by activities and human groups)’[20]

It is evident that trading stores as social spaces do not reflect elements of Zulu social or material culture at any level. They construct new mutual spaces, as architecturally and politically non-partisan structures, that generate their own culture of occupation. Perhaps it is this total otherness, the possibility to act out a different life in an alternative space free from the constraints of culture and tradition that entrenched the concept of the trading store and its implicitness in communities.

Conclusions

The architectural language comprehended through the design of the trading store thus visually translates the hierarchy of space, determined commercial activity, and neutral participation in purchase. The different spaces present a series of spatial transitions: The open outside world is occupied by and accessible to all, as indicated in the transcripts by Cetswayo kaMpande and Ndukwana kaMbengwana. The veranda leading into the store is an openly accessible transition space between inside and out, on which interstitial activities can occur. It is part of the store fabric, yet is not actually ‘inside’ and subject to the rituals that ‘inside’ suggests, and the internal store floor is an enclosed public space. It was a platform used to act out a ritual of purchase, completing a series of social games. The customers come from different cultural groups and have different world-views to the proprietor, and are generally the ‘owners’ of this space. To a large extent, they control the dynamics between themselves as customers and between themselves and the trader. Fundamentally, the organization of the space within the trading store could be considered to function in a similar quasi-egalitarian fashion as the Greek Agora.

Whilst the trading stores have largely closed, the study does provide some room for thought as to the fact that considerations of historic space, certainly, was very different for people of the Southern Nguni, who dwelt in partisan realms determined by power relations, and constructed western space of the white settlers who relied on mutually negotiated spaces as in the polis as reference.

Perhaps understanding the fundamental differences in perceptions of space can begin to interrogate how spaces are constructed in contemporary cities, with new users post-transformation who have different ways of seeing space. This can then begin to re-inscribe value and validity. The ideas of the dynamic, the movement, the path and the event dominate the manner in which the inner cities have changed, and the departure from monument, place and egalitarian space should possibly not be bemoaned, but rather be re-inscribed, and embraced. Perhaps the many remonstrations of mismanagement, filth, litter, and vagrancy in the centre of Pietermaritzburg in the second decade of the twenty first century need to be re-examined through a new lens of spatial usage, and not through habitually learnt western paradigms of ‘doing’.

____________________________________________________________________

Debbie Whelan has a B.Arch. (UND) and a M.Arch. (UND) and BA in Archaeology and Anthropology (UNISA). In 2011, she was awarded a Ph.D. in Social Anthropology (SOAS) focusing on building and memory. She did development work during the democratic elections in 1994 and has worked as a Heritage Officer for the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Heritage Resources Agency, Amafa. She is the director of a research consultancy which focuses on land claims investigations as well as heritage impact assessments. She was an ICOMOS intern in New Mexico in 2000 and carried out a reactive monitoring mission for ICOMOS in 2015. Currently she is Senior Lecturer in the School of Architecture and the Built Environment, University of Lincoln. Her publications are in the areas of indigenous and modern architectural vernaculars, infrastructure history, cultural and historical landscapes, heritage and authenticity.

____________________________________________________________________

[1] Nalini Naidoo, “Fed-up action on litter”. The Witness, 30 April 2013. http://www.news24.com/archives/witness/fed-up-action-on-litter-20150430, Kailene Pillay, “Taking back the city’s streets”. The Witness, 13 March 2017 http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/taking-back-the-citys-streets-20170312, Kailene Pillay, “Vagrants defile Post Office”. The Witness, 5 March 2017 http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/vagrants-defile-post-office-20170305

[2] Heather Peel, Sobantu Village – an administrative history of a Pietermaritzburg Township 1924-1959 (MA Diss., University of Natal, 1987), 4.

[3] Rebecca Hourwich Reyher, Zulu Woman-the life story of Christina Sibiya (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1999 [1948]), 36.

[4] Noni Jabavu, The Ochre People (Johannesburg: Ravan Press1982 [1963]), 65.

[5] Union Government 61/1955, Summary of the Report of the Commission for the Socio-Economic development of the Bantu Areas within the Union of South Africa (Tomlinson Report) (Pretoria, Government Printer, 1955), 90. Please note that the term Bantu, simply meaning ‘the people’ may be considered pejorative in contemporary times but was in common use in the 1950s.

[6] Union Government, Tomlinson Report, 90.

[7] The trading store provided unbiased service in areas in which internecine rivalry was rife: Traders were sensitive to customer needs, but they were business people and not partisan.

[8] Monica Wilson and Leonard Thompson, The Oxford History of South Africa. Vol 1. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), 265.

[9] Hilda Kuper, “The language of sites in the politics of space,” The Anthropology of Space and Place: Locating culture. Ed. Setha Low and Denise Lawrence-Zuniga (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003 [1972]), 253.

[10] Colin Webb and John Wright, A Zulu King Speaks – statements made by Cetswayo kaMpande on the history and customs of his people (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1987), 78.

[11] Colin Webb and John Wright, The James Stuart Archives Volume 4 (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1986), 313.

[13] Webb and Wright, The James Stuart Archives, 313-314

[14] Natal Colony, Natal Code of Native Law 19 of 1891

[15] John Argyle and F. Buthelezi, Zulu Symbolism of right and left in the use of Domestic and Public Space. University of Durban Westville, Association of South African Anthropologists Conference 1992.

[16] Hannah Ahrendt, Between past and future: six exercises in political thought (London, Faber and Faber, 1961), 116.

[17] Ahrendt, Between past and future, 104.

[18] Ronald Lewcock, Early nineteenth century architecture in South Africa: A study of the interaction of two cultures 1795-1837 (Cape Town: AA Balkema, 1965), 130.

[19] H. Marsh, Illustrated catalogue of wood and iron buildings (4thed)(Pietermaritzburg: P Davis and Sons, ca 1915)

[20] Christopher Alexander, A pattern language: Towns, buildings, construction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 941.