Splicing the Western Ghats

In the nexus of urban imaginary and settling imagery the Western Ghats of India is singled out as a distinct zone, a range of hills on the west coast of India. Geologists see it as an escarpment made of layers of settled basalt in the north that turn to gneiss and laterite rich in minerals to the south. Overlaid onto this geology is a distinctive moist deciduous forest that receives the rains of the southwest monsoon. Added to the unique habitat given it by rock and rain, the Ghats is recorded as a place of cultures settled between a particularly active global coast on the Arabian Sea to the west and the Deccan Plateau on the east. In July 2012, UNESCO designated the Western Ghats a World Heritage Site. They see it as one of the hottest ‘hotspots’ of biodiversity and one of the oldest cloud forests that is home to rare species of frogs and flowers, a dwindling population of tigers, a place of ancient practices of agriculture and conservation, sacred groves and much else. But the drive to label it a heritage site is facing stiff opposition from developers, prospectors and politicians, bringing the Ghats to prominence as a leading contested landscape where environment and development, culture and nature, are being positioned as elsewhere in opposition at multiple levels. It has prompted calls for a regional plan.

Rather than operating by zoned land uses on a surface demarcated by geographic lines toward a regional plan, the studio initiated a process of re-imaging the Western Ghats with the assumption that people as well as flora and fauna here do not necessarily settle inside or outside enclaves; they rather splice into a material condition that has a beginning but no end, direction but no destination, trajectory but no enclosure. Water too in the Ghats is not settled within streams and rivers confined by geographic lines; it rather splices into the earth, vegetation and animals that come alive and thrive with each monsoon to transform the Ghats for a time before receding until the next rains.

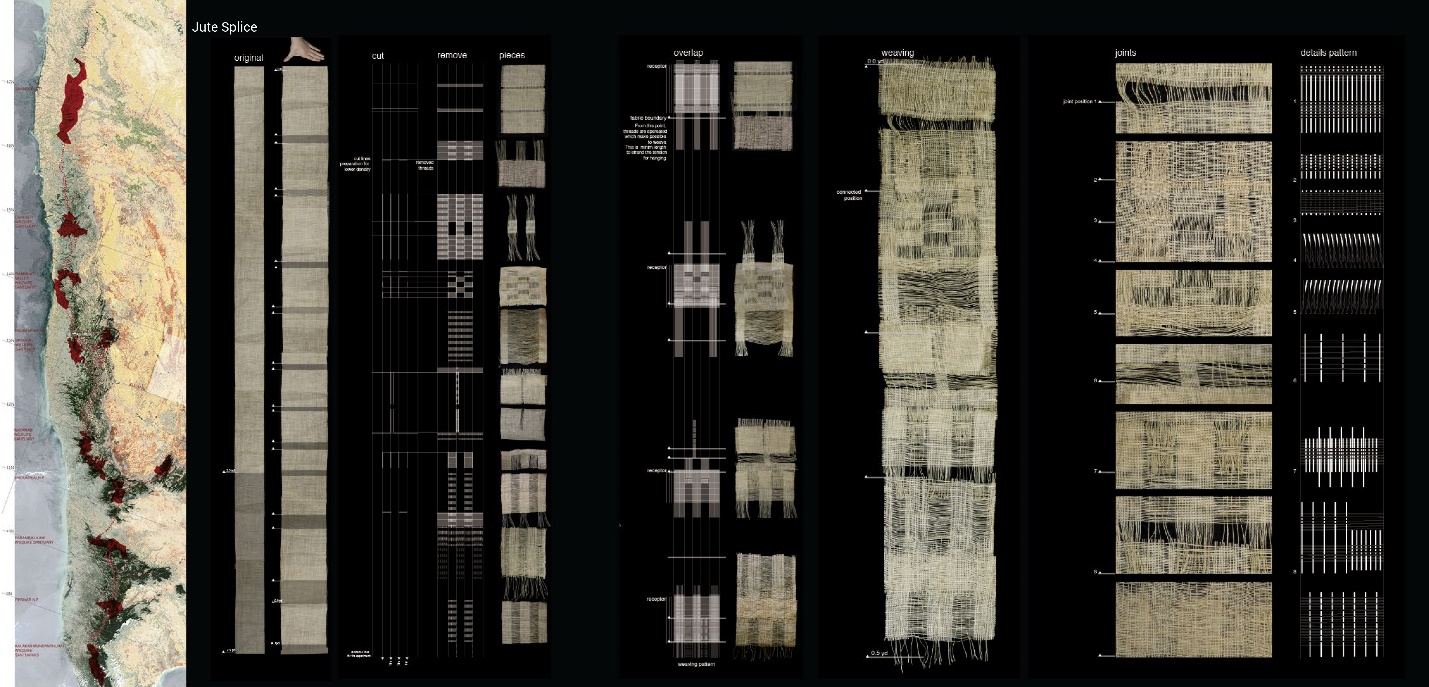

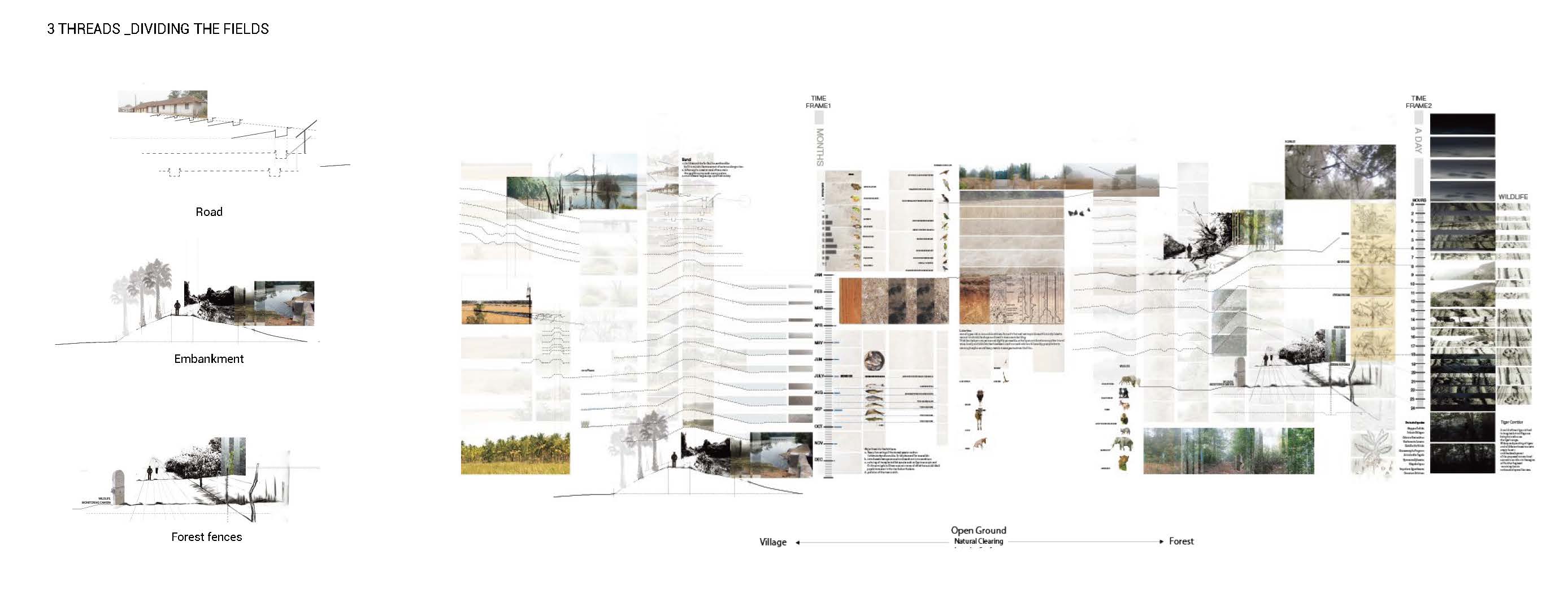

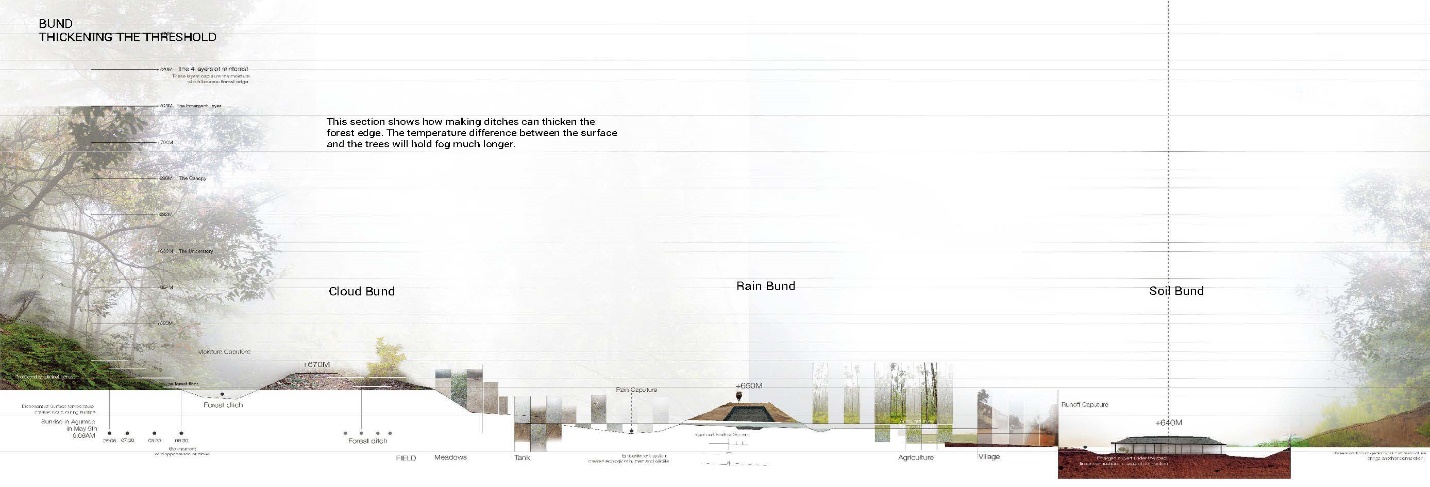

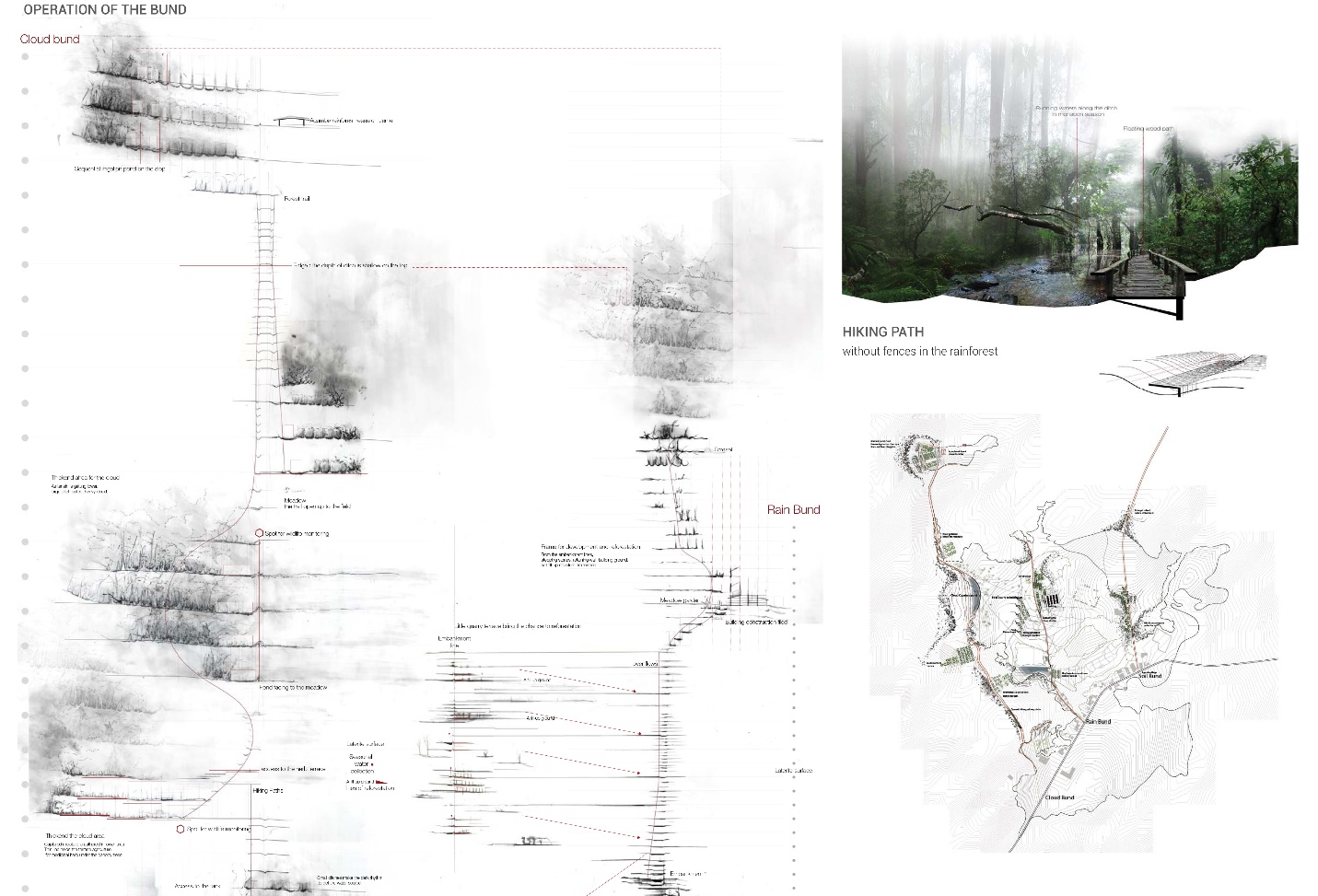

THICKENING THRESHOLDS: Splicing a piece of jute fabric and reflecting on the process of its re-construction structures and agenda for a project. It brings into focus a particular clearing, a meadow in Agumbe, but also a strategy for reconstituting the fabric of the Ghats from the perspective of the tiger, a fabric that has been torn apart by processes of development. Engaging forest fences, bunds (embankments), and roads, the project thickens existing thresholds and ‘threads’ small scale ecologies to create fertile grounds for both human and wildlife movements across the meadow and beyond. (Leeju Kang, School of Design, University of Pennsylvania, 2015)

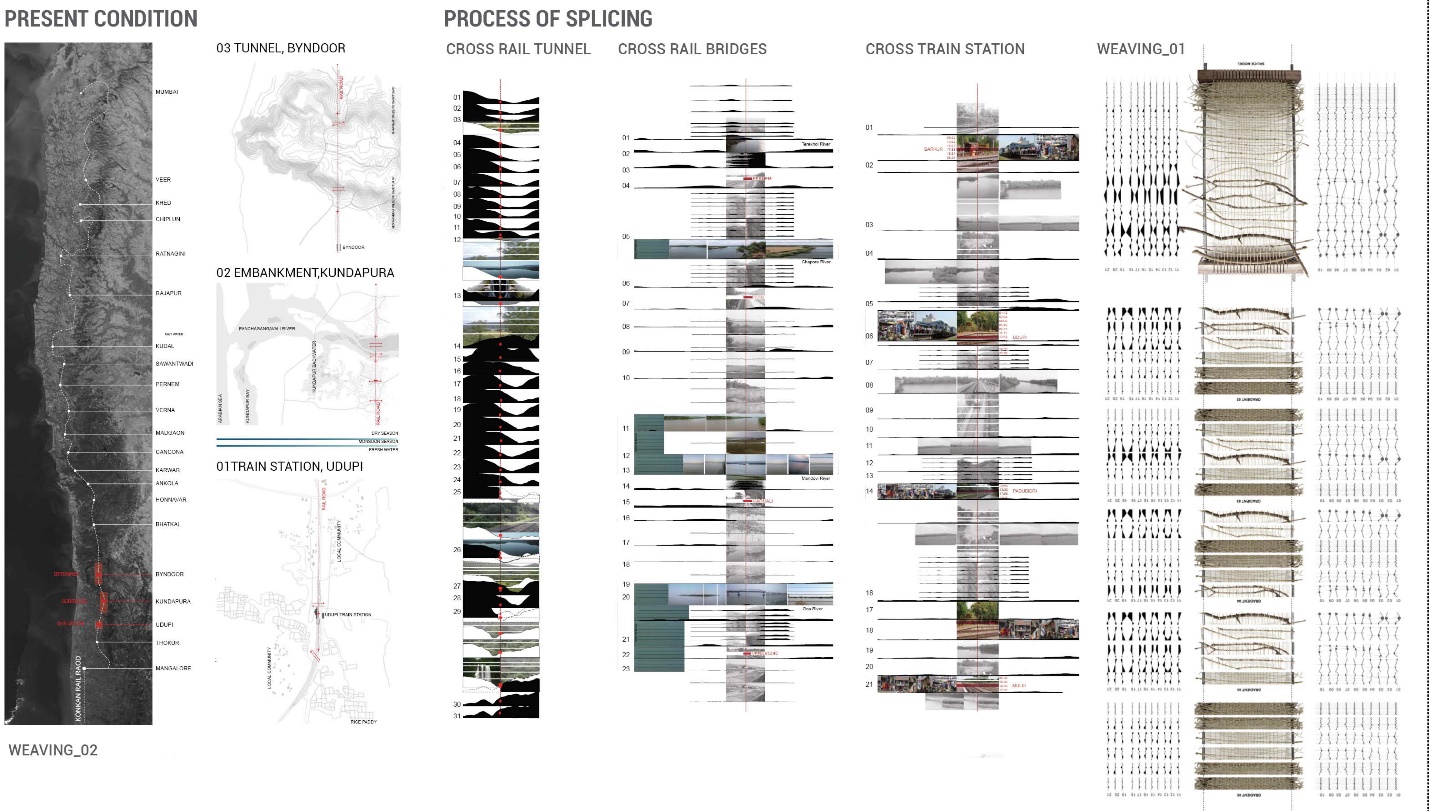

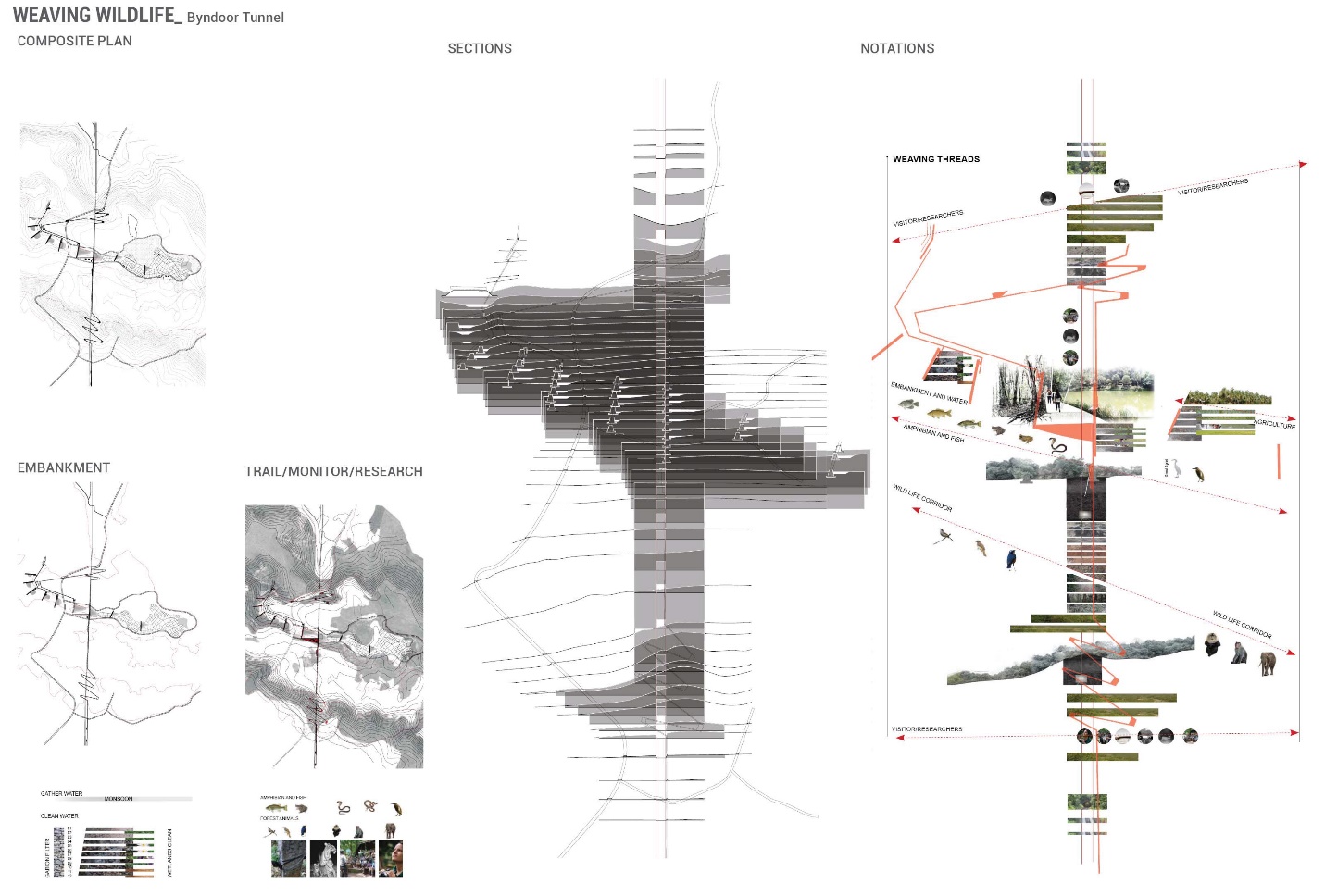

WEAVING RAILWAYS: A material fabrication of wood, sticks, and string initiated the process of reimaging the Konkan Railway as a splice that brings together landscapes of three different conditions in three different zones along the rail. By rethinking the functions of track, embankment, platform, and tunnel as interventions that can engage territories extending from them, Weaving Railway aspires to transform a severing train line that divides communities and wildlife corridors into an interactive field of practices, places, and wildlife bridges. The new trajectories constructed spread their influence physically and programmatically to stimulate local economies and ecological systems. (Ying Liu, School of Design, University of Pennsylvania, 2015)

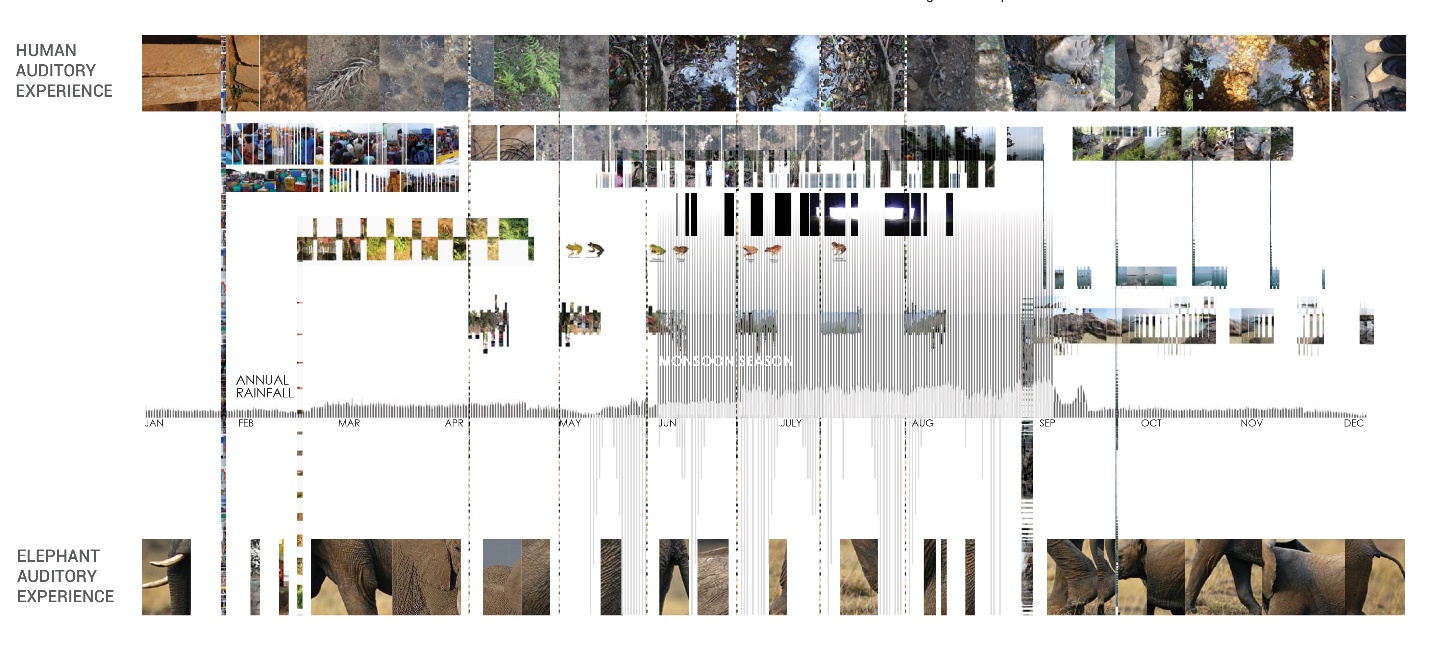

SOUNDFIELD: Images spliced to draw out the intensity, juxtapositions, and duration of sounds within the Western Ghats inspire a way to re-consider human and wildlife corridors within the Ghats. Focusing on elephants who are guided by ecologies of sound, this notation led to a design strategy for negotiating and re-aligning existing areas of conflict between elephant and humans without enforcing boundaries or fences. (Yadan Luo, School of Design, University of Pennsylvania, 2015)

Dilip da Cunha and Anuradha Mathur are architects and professors. They are authors of Deccan Traverses: The Making of Bangalore’s Terrain (2006) and Soak: Mumbai in an Estuary (2009).

Notes

[1] José Ortega y Gasset, “Who Rules the World?” The Revolt of the Masses (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc, 1932), 165

[2] Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1938), 3; Peter Hall, Cities in Civilization, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1998), 7

[3] Quoted in Robert Park, “The City: Suggestions for the Investigation of Human Behavior in the Urban Environment,” Robert E. Park, Ernest W. Burgess, Robert D. McKenzie (eds.), The City (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967), 1

[4] Robert Park, “The City: Suggestions for the Investigation of Human Behavior in the Urban Environment,” Robert E. Park, Ernest W. Burgess, Robert D. McKenzie (eds.), The City (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967)

[5] Louis Wirth, “Urbanism as a Way of Life,” American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 44, No. 1, 1938

[6] The movement was initiated by Ebenezer Howard with the publication in 1898 of To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. He revised and republished it in 1902 as Garden Cities of To-morrow.

[7] Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), 1

[8] M.K. Gandhi, Village Swaraj (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House, 1962), 29

[9] Henri Lefebvre, Writings on Cities, translated and edited by Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996), 148, 158

[10] David Harvey, “The Right to the City,” New Left Review 53, September/October 2008

[11] Melvin M. Webber, “The Post-City Age,” Deadalus, 1968; Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994); Saskia Sassen; Manuel Castells, “Space of Flows, Space of Places: Material for a Theory of Urbanism in the Information Age,” Stephen Graham (ed.), The Cybercities Reader (New York: Routledge, 2004)

[12] Nato Thompson (ed.), Experimental Geography: Radical Approaches to Landscape, Cartography, and Urbanism (New York: Independent Curators International, 2008); Stephen Graham, ed. The Cybercities Reader (New York: Routledge, 2004); Sarai Reader 02: The Cities of Everyday Life (Delhi, 2002)

[13] Rem Koolhaas, “What Ever Happened to Urbanism?” S,M,L,XL (New York: Monacelli Press, 1995).

[14] Ibid., Book II: 18-19, 102

[15] Herodotus, The Histories, Book II: 177, translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt (London: Penguin Books, 2003), 167

[16] Herodotus, The Histories, Book II: 97, translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt (London: Penguin Books, 2003), 132

[17] Archeologist Gordon Childe describes this occurring in two revolutions: an “agricultural revolution” which turned humans from savagery to barbarism and the “urban revolution” which turned them from barbarism to civilization with the advent of literacy and the city.

[18] William Lambton, ‘A Plan of a Mathematical and Geographical Survey extending across the Peninsula of India proposed to be carried into execution by Brigade Major Lambton’, Fort St. George, 10 February 1800, (British Library, P/254/52, 746-47).

[19] Colonel Sir Thomas Holdich, “The Use of Practical Geography Illustrated by Recent Frontier Operations,” in The Geographic Journal, Vol. 13, No. 5 (May, 1899)