Suresh’s childhood was spent between the Wilson Garden area in Bangalore and Kalahalli near Sarjapur, where his mother’s family is from. Now a major metropolitan centre, the then Sarjapur was a village in the outskirts of Bangalore, a very dry area with little options for meaningful agriculture, other than growing Ragi. The villagers had to look for other sources of livelihood. In addition to the milk business, his mother’s family was also into silk production. They were the first to start sericulture in Sarjapur. Sericulture is a laborious work that requires huge manual labour force for feeding and cleaning the silk worms four times a day. Suresh’s large extended families on his mother’s side, especially women, were entirely involved in sericulture. Mulberry, food for the silk worms, was grown in the village lands by pumping water from a huge stonewalled well.

After finishing his Masters in Fine Arts (MFA) at Delhi College of Art, Suresh returned to his village. The land where ragi and mulberry grew until recently, was covered with glass and cement towers, or plotted for future gated communities. Open lands were being turned into closed farmhouses, weekend retreats for the urban elite. Sericulture stopped; silk twisting machines and silk looms that the villagers ran were shut down because of lack of electricity, which was now directed to IT companies. The big stonewalled well that watered the mulberry was now completely dry. Suresh decided to stay in the village and start working from there. A large and empty tile roofed house where once silk worms were reared became his studio.

Rapid transformations, both in the physical and cultural landscape of Bangalore’s outlying areas, and the stories that villagers, who were living witnesses to these changes, told him became the source for Suresh’s work. Materially too, art objects and large installations were created from what was available in the surroundings. The four significant installations he created of this time – Wade, Selfish Tree, Harvest for Better Monsoon and Lifeline – fused the villager’s current conditions, unfulfilled promises of makeover through development, and the materials symbolised past, present and once again the promised future.

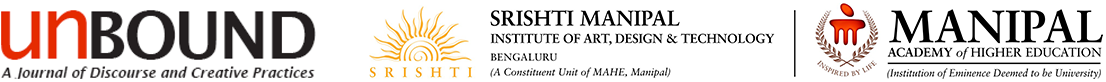

Wade (2005), consists of two locally used grain storage container (wade) shapes fashioned from steel rebars. Traditionally, Wades were made from terracotta and buried into the walls, or as stand-alone Wades made of straw and red soil. One of the silo’s exterior in the installation is covered with bricks; these bricks are not real bricks made of clay, but instead they were stitched from Flex, a material widely used in advertising hoardings. The visible outer layers of these flex bricks were printed with images of new apartment complexes and gated communities promoted on the flex hoardings dotting the city of Bangalore. The brick shaped pouches were filled with ragi that Suresh collected from villagers who had stopped cultivating lands, as they were caught between severe drought and the onslaught of development. The second Wade shape lay bare with its steel skeleton; ragi in the bottom with toys of construction vehicles, placed on the grain. The toys too, like ragi, were collected from local residents.

Suresh Kumar, Wade, 2005. 4 x 8 feet. Steel, flex and ragi millet and toys. Curtesy of the artist.

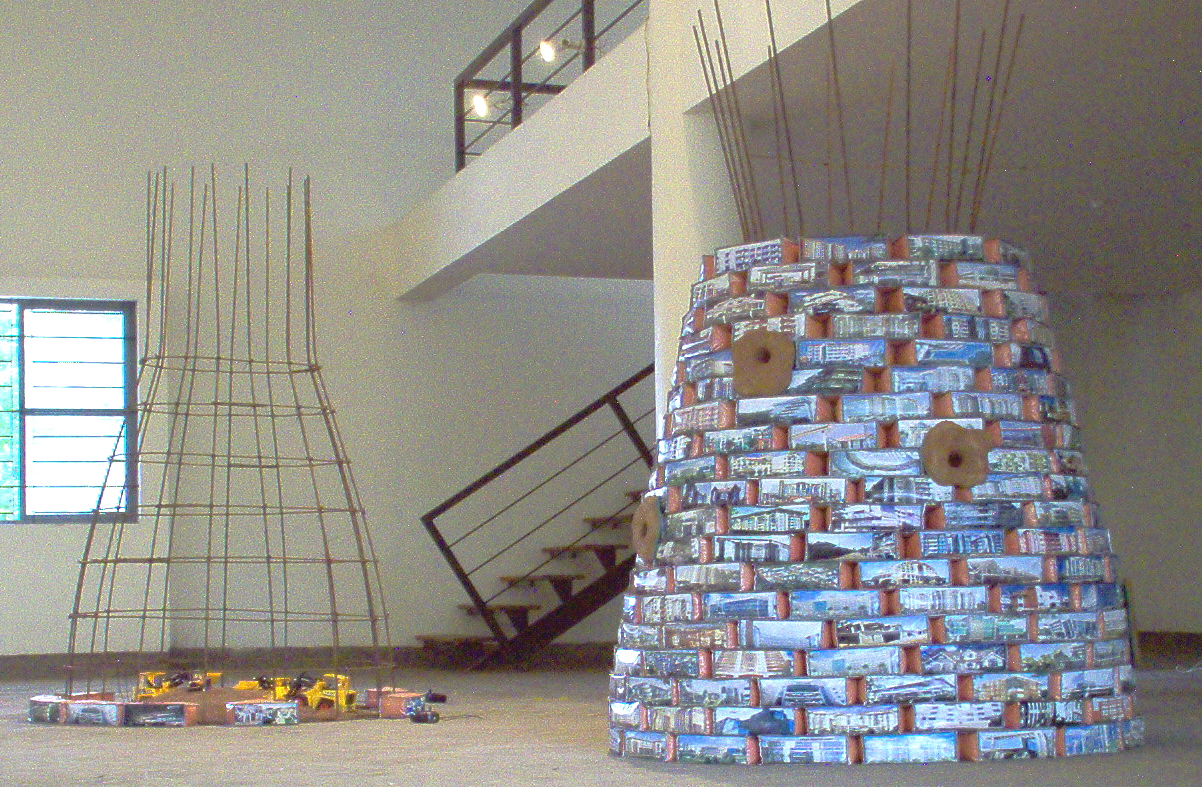

The second installation of this series entitled Harvest for Better Monsoon (2003) is a woven silk sari encrusted with dead ragi sprouts that Suresh picked up from his village fields. Failed rains and dried-up ground water had killed the fledgling plants. The sari was draped at an angle from ceiling to floor and underneath, on the floor, was a bed of unevenly shaped terracotta tiles arranged to look like withered fields. A weaver who had given-up weaving, because the promised development and income from sericulture never materialised, wove the sari. The silk yarn used was remnants that Suresh found lying around in former weavers homes. Encouraged by the government and with promises of jobs and larger income, the villagers in Srajapur had adopted sericulture and invested heavily, by borrowing, on power looms in the 90s. By the turn of the century, the government had moved on to new things. Now the policy of liberalization inaugurated second modernity in India and Bangalore was the first to adopt it with enthusiasm. IT was the new promise of prosperity and only the urbane and educated had access to it. Power looms in Suresh’s village went silent. Voracious computers in the IT parks were consuming the electricity needed to run the looms. The government preferred IT to weaving. Failed monsoons combined with pressure on ground water, owing to new constructions, resulted in drying the open wells first, and then followed by deeply dug bore wells. Harvest for Better Monsoon like his first installation Wade folds together diverse temporalities, spatial transformations and the materials rooted in particular time and space.

Suresh Kumar, Harvest for Better Monsoon, 2003. 4 x 18 feet. Silk fabric, dried ragi sprouts, terracota and found objects.

Suresh Kumar, Harvest for Better Monsoon, 2003, details. Courtesy of the artist.

Suresh Kumar, Harvest for Better Monsoon, 2003, details. Courtesy of the artist.

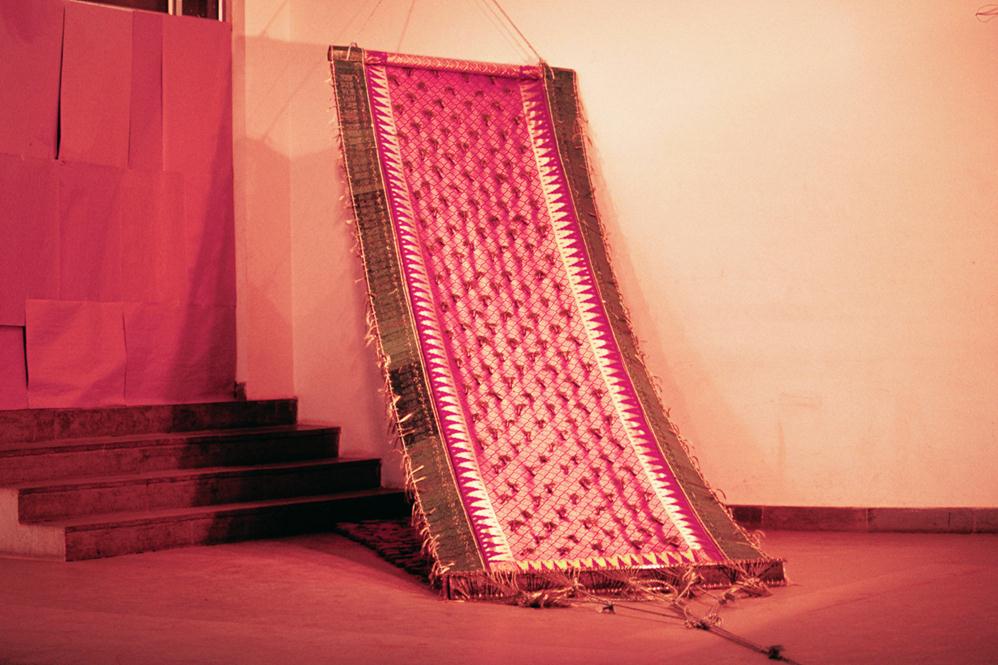

Lifeline (2002-03), the third installation in this series, consists of railway tracks in wood laid on a ramp. The tracks are so well carved and crafted with texture that they invoke tactile and visual sensations of the iron tracks on a railway line. Instead of stone ballast, the sleepers are filled with the empty plastic cups used ubiquitously for serving tea and coffee in Indian Railways and discarded after use on to the tracks. At the foot of the ramp, both rail tracks separate out into coils. On the other elevated end of the installation, although interrupted, the tracks give the visual sensation of endless continuity. The brick wall like visible exterior of the ramp is covered with sculptural reliefs of workers laying the railway tracks. Lifeline is another invocation of failed promises of jobs and prosperity that villagers had experienced. The counterpart of the Lifeline rail track cuts through Suresh’s father’s lands in his paternal village near Chandapura, about 20 kilometres further away from Sarjapur. In the 60s, his father and the other villagers had worked on building the line, which was to bring jobs and livelihood to the villagers. This lasted only for the duration the railway line was constructed, after which the villagers settled back to tilling the dry land.

Suresh Kumar, Lifeline, 2002-03. 12 x 5 feet. Fabricated and painted wood, terracotta and disposable plastic cups. Courtesy of the artist.

Suresh Kumar, Lifeline, 2002-03, details. Courtesy of the artist.

Suresh Kumar, Lifeline, 2002-03, details. Courtesy of the artist.

The forth installation that Suresh created in this series, the Selfish Tree (2001-02), has a slightly different take, but conceptually aligns with his three previous works. In the village, where Suresh was living and working after his return from Delhi, he found a dried-up jackfruit tree in his uncle’s front yard. He had heard him family tell many stories about this tree; one story in particular interested him. The tree would have plenty of fruits every year, but the family could eat none since every fruit would rot before it ripened. This peculiar nature of the tree and its fruit intrigued the artist; he decided to turn the dried tree into a work of art, and the stories about the tree the narrative for his installation. The Selfish Tree consists of the dried trunk of this jackfruit tree split into three sections. Two sections lay on the ground while the third is suspended in the air supported by three arches based on the sections on the ground. The outer part of the tree trunk sections on the ground are carved like exteriors of jackfruit and spray-painted in yellow and green, so that if the sections are assembled vertically, it would look like stacked up jackfruits. In the interiors of the grounded sections, using thumb tags, the story of the Selfish Tree is written in Brail script. On both sides of the suspended section, small yellow coloured wooden pegs are inserted into the wood, simulating the jackfruit seeds and flesh. Suresh fashioned over 2000 small pegs by hand and drilled holes into the wood to insert them. On one end of all three sections, electrical wires with exposed strands of copper look like tree roots and the arches supporting the suspended section too are wrapped with electrical wires that Suresh found in his uncle’s house.

Suresh Kumar, Selfish Tree, 2001-02. 12 x 15 feet. Carved and painted Jackfruit tree trunk, synthetic veneer, steel rods and insulated copper wire. Courtesy of the artist.